Healthy wetlands provide food and fodder for the species and people living around them. But over-exploiting these resources can lead to degradation, which in turn, affects the communities living on the wetlands.

“Conservation in rural context means creating livelihood opportunities for the poor while in urban areas it is about convincing people to be more sensible about their lifestyle.”

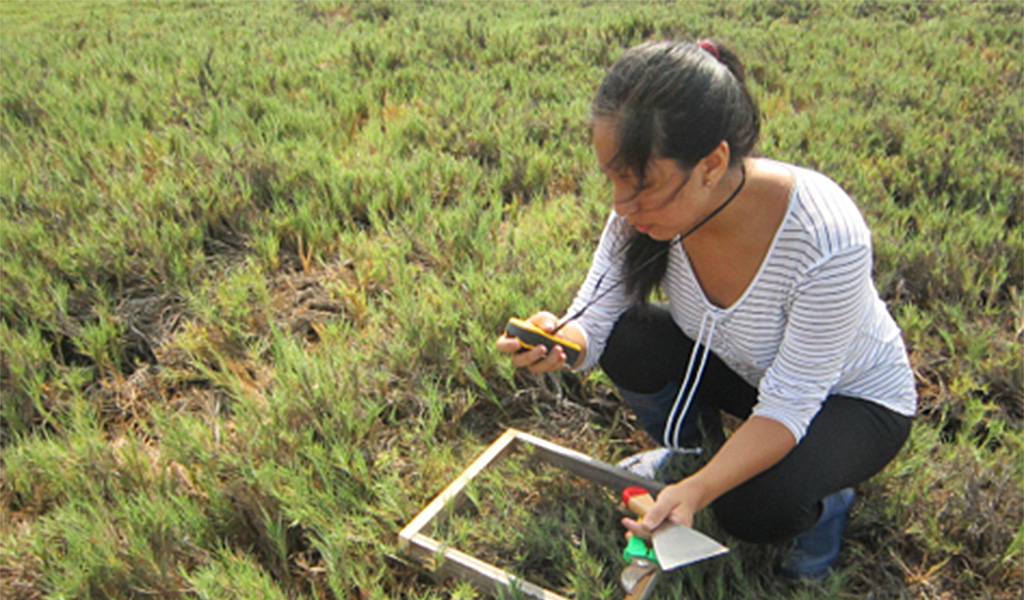

Getting the balance right is a major challenge for the Indian village of Hatimuria, which relies on a wetland called Bherbheri Beel in the state of Assam. Tanvi Hussain, a 29 year-old wetland ambassador, PhD student and scientist from the region works on natural resource conservation with the communities who live around this wetland.

“I am deeply moved by the wonderful balance of nature but distressed by the dilapidated condition of many such wetlands, forests and other areas. Conservation in rural context means creating livelihood opportunities for the poor while in urban areas it is about convincing people to be more sensible about their lifestyle,” says Tanvi.

Bherberi beel during sunset.

Tanvi is a Project Scientist as part of a state government organisation Assam Science Technology and Environment Council (ASTEC) which works with central and state government. She part of a project to build the resilience of the community of Hatimuria dependent on the Bherbheri beel – beel being the local term used for wetlands and ponds in Assam – and help it adapt to the impacts of climate change.

This involves making livelihood activities in the village such as farming, water harvesting, irrigation of farmland, cattle rearing, energy sources “climate friendly”. We work together with the residents of the village and help them to become aware of the impacts of climate change and prepare them for climate change induced threats, says Tanvi.

“After the fishing period harvest all the remaining fish were caught by pumping out the water in the wetland, lowering the village’s ground water table and contributing to water scarcity.”

One particular focus has been to help villagers have a better understanding of how the wetland functions and how it is connected to water availability. Tanvi explains that the auctioning off of the wetland [harvest] during the fishing season to local businessmen led to a practice that was contributing to degradation. After the fishing period harvest, all the remaining fish were caught by pumping out the water in the wetland, lowering the village’s ground water table and contributing to water scarcity.

“The auctioning off of these wetlands and diversion of water has also been putting South Asian river dolphins, migratory birds, other animals and plants at risk and locals are ill-equipped to deal with the changes. That is why we want to help them,” she says.

Local workshop to inform people about the importance of their wetland and how to keep it clean.

As part of the efforts to raise awareness, ASTEC is issuing handbooks on the local biodiversity. Children are being taught about climate change and resilient practices, while local youth are taught skills such as wild bee-keeping and honey extraction, bamboo craft and nature walks – practices that can help sustain the balance across the wetland.

Women are being supported to boost income through weaving. Creating these sorts of alternative livelihoods will helps boost villagers’ financial conditions, which avoids the need to auctioning off the wetland for monetary benefits.

“Hatimuria will serve as an example to encourage other villages to get involved with the council’s supportive measures and to become self-sufficient.”

The longer-term vision, according to Tanvi, is to restore the ecosystem and create possibilities for eco-tourism throughout the area. The village is situated just 2.5 km away from Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary which houses a host of majestic animals including the one-horned rhinoceros, Asiatic wild buffalo, elephants, swamp deer and migratory birds from different parts of the world between November and March every year.

Tourists come from across India and all over the world to marvel at the area’s natural beauty. Managing the Bherbheri wetland throughout the year, particularly at the time of auction (November to March) will help make it attractive for visitors, creating both an inherent and monetary value for the wetland and its people.

Tanvi says: “I am very proud that we have been able to work with the local people and that we have reached consensus on the importance of the wetland and the function a wetland has in support the ecosystem. Hatimuria will serve as an example to encourage other villages to get involved with the council’s supportive measures and to become self-sufficient.”