What started as a police complaint about the destruction of mangroves in 2016 turned into a passion for conserving wetlands for the Agarwals. This Navi Mumbai couple, both in their 50s, has been fighting to save 80 hectares of wetlands in Navi Mumbai that are home to thousands of flamingos. The wetlands were proposed to be converted into a golf course and residential complex but in 2018, based on their petition, the Bombay High Court (HC) quashed a notification to this effect. The forest department now plans to declare the area a conservation reserve but is facing resistance from within the government.

“ I strongly felt the people’s hopelessness because they lost the hope of land and livelihood.”

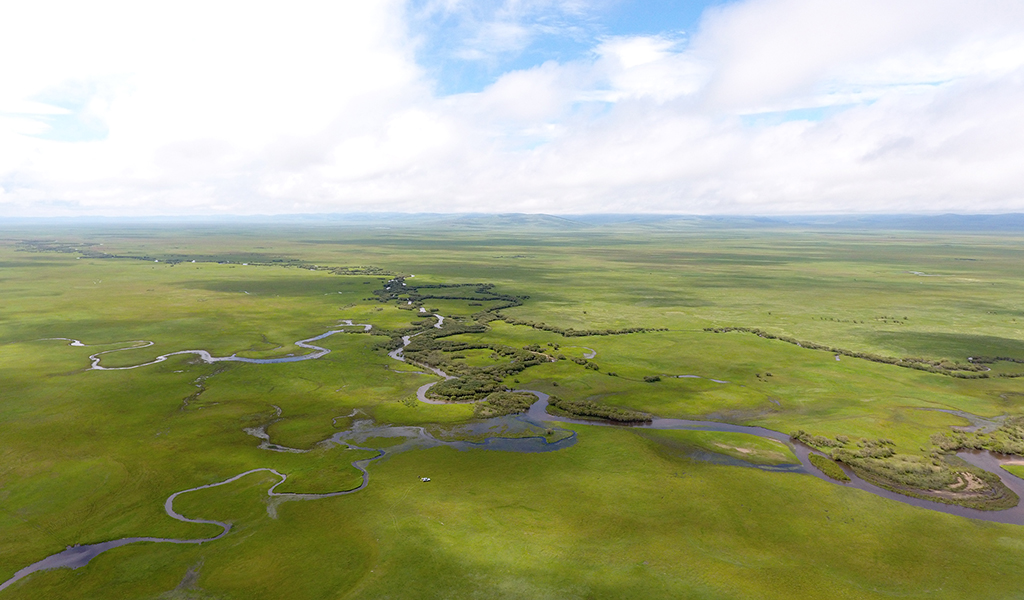

Navi Mumbai, a satellite city of Mumbai, is more scenic and serene as compared to the commercial capital owing to large number of trees, open spaces, mangroves, mudflats, salt pans and a creek. Thousands of migratory birds visit the area every year.

Several residents of Navi Mumbai have been fighting to save their local environment, specifically the wetlands, from destruction for years now. These wetlands are under threat from proposed construction for residential and other infrastructure projects. One example is a movement to save Panje wetlands in Uran, a part of Navi Mumbai, where the core wetland covers about 213 hectares and is an important site for migratory birds. This wetland is also close to a proposed airport. Not far from Panje are two more wetlands – one, measuring 13 hectares, behind Training Ship Chanakya (TSC), a maritime academy on Palm Beach Road and another near NRI Complex, a residential complex in Navi Mumbai’s Seawoods area. The NRI Complex wetland is located south of TSC with an area of around 20 hectares. While these wetlands constitute a small percentage of the area of Navi Mumbai, they support more than a hundred species and most of them are migratory with declining populations around the globe.

Navi Mumbai, a satellite city of Mumbai, is very scenic owing to the large number of trees, open spaces, mangroves, mudflats, salt pans and a creek. that find its home there Thousands of migratory birds visit the area every year.

Sunil and Shruti Agarwal and their two children, moved to NRI Complex in 2016. On one of their morning walks, they saw an instance of mangrove destruction. They quizzed the labourers and eventually, an FIR was filed at NRI Complex police station. They have been fighting against the destruction of mangroves and these wetlands since then.

“We had not been environmental activists before we got into this issue. We had fought against defacement of Navi Mumbai due to hoardings in the past. Even today if you ask me the definition of wetlands, I won’t be able to tell you. But all I can understand is something wrong is happening,” said Shruti Agarwal, a television producer. The couple also raised alarm when hundreds of trees were cut at the wetland citing permissions from local authorities. As work on the wetlands got more demanding, Sunil, a self-employed chartered accountant and Shruti decided to take a break. Now their children also help them in their cause.

In a Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) report published in 2019 titled ‘Coastal Wetlands and Waterbirds of Navi Mumbai: Current Status’, both T.S. Chanakya (TSC) wetlands and NRI complex (Talawe) wetlands find an elaborate mention. The TSC wetland has 21 bird species including four near threatened species and one vulnerable species. Between January and September 2018, BNHS recorded waterbirds on the TSC wetlands including near threatened species (IUCN status) such as painted stork, lesser flamingo, Eurasian curlew and curlew sandpiper. These species were also observed at the NRI Complex wetland during this period. The NRI Complex wetland hosts 37 waterbird species, including four near threatened and one vulnerable species, according to the report.

According to documents from City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO), the agency responsible for the proposed infrastructure works in the area, there are three plots in question, viz, pockets A, C and D located in Seawoods, Navi Mumbai. Of these, zone changes have been made in Pocket A (20 hectares) and D (0.85 hectares) – and proposed in Pocket C (47 hectares) – to facilitate the development of the golf course and residential area and make the areas economically viable. The golf course, approximately under 20 hectares, is planned on parts of NRI wetlands while the residential complex will come up on a 13 hectare plot part of TSC wetlands. The changes were made according to Maharashtra government’s notification of October 5, 2016, for a sanctioned modification to Navi Mumbai’s Development Plan.

The BNHS also observed near threatened species (IUCN status) such as painted stork, lesser flamingo, Eurasian curlew and curlew sandpiper in the TSC wetlands.

However, the same BNHS report has warned of landfilling, excavation of soil, intensive fishing and overcrowding as threats to the TSC and NRI wetlands. Therefore, as a conservation and management action, the report has suggested, “land reclamation work should be strictly prohibited at this site. This wetland (TSC) should be declared amongst protected areas associated with Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary (TCFS) because water birds from the sanctuary are using it as high tide roost when sanctuary gets flooded during high tide.” For NRI wetlands also, the report has suggested managing traditional fishing practices in a way to manage the water level in the wetland for birds and that crowds should be regulated.

Sub-unit Panvel that consist of the T.S. Chanakya Wetlands and NRI Complex wetlands finds a mention in the National Wetland Inventory and Assessment (NWIA) Atlas.

Even though NWIA does not list all 2.01 lakh wetlands covered under it, a Bombay HC order referred to TSC and NRI wetlands as part of NWIA.

“If these wetlands are declared a conservation reserve, it will be a victory for us. These wetlands are protected by Supreme Court (SC) order but construction could start just because of a CIDCO order. If these 2.01 lakh wetlands are protected as per SC order, it is only SC that can change this status,” said Sunil.

“We had no language in common, but I was surprised at how well we were able to communicate through art. We gave them a sense of pride about the art works and their wetland.”

“For every year we delay it (the golf course project), we prevent environmental destruction. We feel like we are owners (guardians) of 80 hectares of land. We are also happy that we have inspired people to save their local environment as well,” said Shruti.

Navi Mumbai’s changing land use has contributed to the current geography of its wetlands. Till the 1970s, it was covered with large expanses of salt pans and paddy fields, notes the BNHS report. Tide gates regulated tidal water for agriculture, salt farming and fishing, but these traditional practices declined by the 1980s. Once the region started to get developed into a metropolitan area, increasing land prices, changing hydrology and economy of this region due to construction activities, government policies and changing lifestyles could have made people abandon farming and fishing, notes BNHS in its report. “This might have brought transformation in this region — new wetlands were formed naturally in abandoned salt pans and paddy fields and artificially by soil excavation — existing wetlands became shallow or disappeared due to heavy siltation and landfilling and along with uncultivated and unmanaged lands, they were replaced by prolific growth of mangroves and scrubs,” it noted.

“People point out to us that where we are living right now also used to be a wetland before. I say to them, “Alright, but does that mean we let the last of wetlands also be destroyed?” Just because it happened once doesn’t mean we should let it happen again,” says Shruti.

About 100-200 citizens take part in the protests to save Navi Mumbai’s environment. They are mobilised on social media. On the importance of citizen activism, Shruti adds, “We had not been environmental activists before we got into this issue… When we were working against hoardings, we exposed a lot of people. There was a defamation case against Sunil also but we are undeterred. Environment became our focus when we shifted here… Our children also actively help us. We are also happy that we have inspired people to save their local environment as well.”

Citizens who joined the movement to protect Navi Mumbai’s urban wetlands at Talawe. Photo from Sunil Agarwal.

“People point out to us that where we are living right now also used to be a wetland before. I say to them, “Alright, but does that mean we let the last of wetlands also be destroyed?” Just because it happened once doesn’t mean we should let it happen again,” says Shruti.

Navi Mumbai resident Vinod Punshi said, “When CIDCO came to London and approached the Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) living there, one of the selling points was an 18-hole international standard golf course. Later, the plan was amended to a nine-hole golf course but then that also did not seem feasible. That is why a golf course was built at Kharghar. They just want this land bank.”

The Agarwals who mobilised residents of the Seawoods area and have been opposing the golf course at the wetland site filed a PIL in the matter in 2018 that was clubbed with an existing PIL of 2013 filed by Navi Mumbai Environment Preservation Society and Punshi. A judgment was pronounced on November 1, 2018, which relied on a Supreme Court judgment that emphasises the doctrine of public trust. While referring to it, HC states, “…there is a total ban on reclamation of wetlands identified under NWIA. There is a ban on any permanent construction on such identified wetlands.”

The TSC wetland has 21 bird species including four near threatened species and one vulnerable species.

In the order, HC further stated, “The agenda note (of 435th meeting of Board of Directors of CIDCO held on May 9, 2002, which proposed modification of Development Plan) will show that the decision of proposing change of DP was taken mainly for commercial reasons. There is no greater public interest reflected from the agenda note for converting the water bodies in NDZ into a golf course and residential complex.”

The court further noted, “Moreover there is nothing placed on record to show that the impact on the ecosystem and environment of filling in water bodies for making construction of residential complex and for making golf course was assessed or at least such assessments were made available to the Planning Authority or the State government… Therefore, we have no manner of doubt that the impugned notification is illegal and is liable to be struck down,” the court noted. The court passed an order quashing the notification, ordered reservations provided therein cannot be implemented, allowed the wetlands to continue to remain protected as per Apex Court order.

According to documents from CIDCO, VC and MD Bhushan Gagrani had written to the state Environment Department on September 9, 2016, stating that it is a matter of grave concern for the city of Navi Mumbai that large chunks of developable land have been included in the NWIA. “The wetland delineation has been carried out at 1:50000 scale and there are anomalies which are primarily due to errors in drafting maps, confusions in identification in case of smaller land pockets, apparent similarities in mangroves and terrestrial vegetation and lack of site verification. The Atlas has been prepared independent of any consultation of the legally incumbent Development Plan or the concerned Development Authority. Since the entire Navi Mumbai area is under development as per the planning approach already frozen as far back as in 1979 following Wetland Atlas in toto will not be possible due to mismatches/errors narrated above.” Therefore, the CIDCO MD stated that there is no important wetland around Navi Mumbai notified area.

Sunil and Shruti Agarwal, both in their 50s, have been fighting to save 80 hectares of wetlands in Navi Mumbai that are home to thousands of flamingos.

After the HC order, the project contractor and CIDCO moved the Supreme Court and has secured a stay on the HC order.

Meanwhile, the Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary (TCFS) plan 2019-20 to 2029-30 has included a chapter titled Satellite Wetland Management and Conservation Plan. It refers to the aforementioned BNHS report and cites six satellite wetlands of the TCFS including TSC and NRI wetlands and even suggested an action plan for their conservation.

Therefore, in April 2020, the Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (APCCF)- Mangrove Cell Virendra Tiwari wrote to CIDCO and district administrations of Thane and Raigad asking for comments since the Cell intended to propose protection and conservation measures for these six wetlands as per Wildlife Act (for eg. declaration of conservation reserves, etc).

CIDCO wrote back to APCCF on July 21, 2020 stating, “..this is to inform you that CIDCO had carried out a scientific survey in Navi Mumbai area in 2016 with reference to the wetland atlas published by GoI. As per the report of this survey, these five locations are not wetlands.” While referring to the TSC and NRI wetlands, CIDCO has stated that the areas used to be salt pan lands and several ponds were created hereafter fishermen broke bunds to do fishing here. Besides, CIDCO cited another BNHS report contradicting the one mentioned above. The said report had stated that ‘Navi Mumbai International Airport site and adjoining areas should be made unattractive for birds.’ Apart from the fact the HC order was stayed by SC, CIDCO has also cited a letter by Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, Nagpur to State Revenue and Forest Department on March 3, 2016 “to not propose the bird sanctuary at NRI complex and behind TSC Chanakya locations.”

Based on this CIDCO letter, APCCF has now written to BNHS on July 30, 2020, asking for comments.

When asked about the latest development, Tiwari said, “If the land is maintained as it is and birds can continue to visit the area, nobody would have an issue. Environment department has to take a call now. Declaring conservation reserve will require owner’s consent as land does not belong to us.”

CIDCO MD Sanjay Mukherjee did not comment on the matter.

This story, authored by Tanvi Deshpande, was first published by Mongabay India under the Wetland Champions series and has been republished with permission.